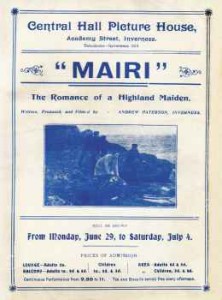

‘Mairi: The Romance of a Highland

Maiden’ premiered in May 1913.

ANDREW PATERSON began experimenting with moving film in the summer of 1912, making what is believed to be one of Scotland’s earliest narrative films, almost certainly the first to be made in the Scottish Highlands. Paterson used the natural landscape of the coastline of North Kessock on the Moray Firth as the setting for his silent movie about romance and whisky smuggling.

the shoreline of

North Kessock in

later years.

Paterson bought an early cine camera for £300 from a Gaumont Graphic salesman in 1912, and during the spring the storyline was written by Paterson and his wife Jenny.

Paterson owned a holiday cottage in North Kessock where the family stayed each summer; knowing the area well, he chose locations that were close by in order to facilitate transport of the camera, equipment, and cast. Locations included the shoreline east of the present Kessock Bridge at Kilmuir, below Croft Downie (ex-Craigton Cottage), with possibly an exterior scene filmed at Kessock House.

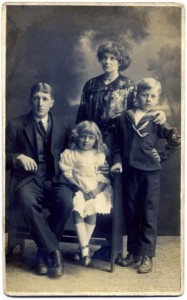

Evelyn Duguid, Dan Munro and Jack Maguire.

This scene was possibly filmed outside

Kessock House, but film-making didn’t disrupt

the normal routine. In the background a

gardener can be seen trimming the hedge.

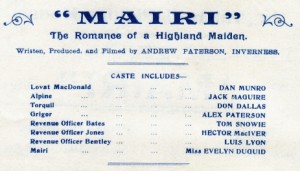

Paterson was much involved with amateur theatricals in Inverness and sourced his cast of eight from local actors. He himself directed and photographed the film. Titled Mairi: The Romance of a Highland Maiden, the film is the dramatised account of a young girl in love with a Revenue Officer who is caught up in a fight to catch smugglers. At one point there is a scene where actors Tom Snowie and Donald Dallas are fighting on a cliff top, before Snowie is exchanged for a dummy and thrown over the edge. It is a brilliant example of early special effects and the film stands in comparison with most of the professionally made films of that time, a considerable achievement for a photographer and cast without any previous film-making experience.

The film premiered at a private screening in May 1913, and one reviewer wrote: “A private view was given on Saturday, with complete success, of a cinematograph film taken by Mr Andrew Paterson, photographic artist, by whom the theme also was composed. The subject of the picture is Mairi, a Highland story. It shows the illicit distillation of whisky in a cave on the shore of the Black Isle, and exciting encounters among the rocks, between Highland smugglers and preventive men. Love interest is imparted to the drama by Mairi, a Highland girl, who is wooed and won by a young English exciseman. The drama was acted on the spot by a company of amateur actors, who admirably filled their roles…We understand that the film has been acquired by Gaumont, London, who supply pictures for exhibition in all parts of the world.”

House in Academy Street

was built in 1912. Renamed

the Empire Theatre in 1934

it was demolished in 1971.

The Highland Times also reported on the preview screening: “CINEMA DRAMA PRODUCED AT KESSOCK…a private view was given in the Central Hall Picture House of a cinematograph drama film taken by Mr Andrew Paterson, photographic artist, at Kessock. The title of the drama is Mairi (a Highland Romance)…The picture is an admirable one in every respect, and Gaumont, London, who have acquired the film, have expressed themselves delighted with it. It is a smuggling story, and shows the illicit distillation of whisky in a cave on the shore of the Black Isle. There are exciting encounters among the rocks between the excise men and the smugglers, and the inevitable love interest is introduced ingeniously by Mairi, a Highland lass, being wooed and won by a young and gallant excise man. The drama was acted at Kilmuir and the vicinity by a company of amateurs, who have acquitted themselves in a very creditable manner. The film is 1,000 feet in length, and should be the forerunner of many an interesting play produced amidst the scenic grandeur of the Highland Capital.”

on North Kessock.

Mairi premiered to the public in the Central Hall Picture House on Sunday 29th June 1913 with continuous performances from 2.30pm to 11.00pm, with tea and biscuits served free every afternoon. (There is a popular misconception that the film was first shown to the public in the Central Hall Picture House on 20th May 1912. However, this theatre did not open until December of that year.)

Both 20-year-old leading man Tom Snowie and Donald Dallas performed in many local stage productions of Rob Roy, with Snowie making the role of Rob Roy his own.

Donald Dallas, better known as Dan, was a gym teacher, strong-man, heavyweight athlete, actor, comedian, singer, and entertainer. He was one of Inverness’s great characters and is remembered for his nose – ‘the nose that launched a thousand quips’ – and although only 5ft 5in, and despite lack of qualifications, he taught ‘drill’ in local schools, including the Inverness Royal Academy. He was a reasonably successful folk singer and old 78rpm records of his recordings are quite collectible today. In his 1932 memoirs he wrote: “…I wonder how many of the younger generation know that a film was actually produced with local actors in the cast. It was named Mairi and was written and produced by Mr Andrew Paterson, photographer, the shots being taken over at North Kessock. It was a story of smuggling days, and when shown in the Central Hall in 1913 the place was packed out.” He died in 1946.

Donald Dallas (right) in later years.

Tom Snowie was a local cabinet maker. Tall, of fine physique and commanding presence, Snowie made an imposing Rob Roy in his Highland garb. He was later a manager of the old Central Hall Picture House but never mentioned his participation in the Paterson film during his lifetime, and his grandson only learned about the existence of the film when it was shown at Eden Court Theatre in 2012. Tom Snowie died in 1972.

Mairi was portrayed by 20-year-old Evelyn Duguid. The daughter of a banker, she was also well known in local theatrical circles, especially as a singer. She too appeared in Rob Roy as Diana Vernon in the 1915 production. A reviewer wrote of her, “The part was earnestly and sympathetically sustained in acting, speaking, and singing.”

as Mairi.

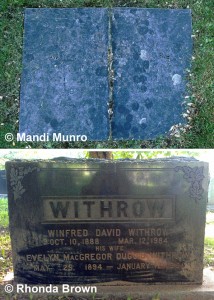

In 1920 Evelyn married Canadian barrister Winfred Withrow, moving with him to Canada and settling in Wolfville. She is remembered there as “a vital, enthusiastic woman, with a passion for all things Scottish, who entertained often at the large brick Withrow home on King Street.” She was described as “the spirit and life of the Celtic Society” and encouraged the learning of Scottish country dances. The Withrows enjoyed sailing and an active social life in the summer at their cottage on Aylesford Lake. She still pursued amateur dramatics and was involved with The Chimes of Normandy in 1922 and The Trojan Women in 1935. Evelyn died in 1961. (Her birth date was noted as 1894, but it was really 1892. Like a lot of actresses, it seems Evelyn at some time may have shaved a couple of years off her age.)

Andrew Paterson himself made a brief foray into making documentaries, including two short films of Scottish scenery on behalf of the old Highland Railway Company, taken from the footplate of one of their railway engines. He stopped making films because he was not that impressed by the new moving picture technique. When interviewed for the Glasgow Herald in 1983, his son Hector said: “He asked the Gaumont Graphic people to take the camera back, which they did with regret, but my father insisted that portrait photography for him was much more important.” As a portrait photographer, it would have seemed logical for Paterson to feature a substantial amount of facial close-ups in the film, a trait of the silent movies where close-ups were used to display emotion, but, interestingly, there are none in the film at all.

In 1953 the film was re-edited by James Nairn, who added a written introduction, intertitles and credits. This is the version that has since been preserved. It was shown again in 1983 at the Eden Court Theatre as part of a promotion by the Scottish Film Archive and again in November 2012 as part of the The Lost Art of the Film Explainer presentation.

the North Kessock shoreline.

Evelyn Duguid Withrow in

Willowbank, Wolfville,

Nova Scotia.

Scottish storyteller and narrator Andy Cannon raised the interesting possibility that the existing film is incomplete, that there might be some scenes missing from the start. The programme synopsis that Paterson published in 1913 begins with a few different scenes, establishing shots to introduce the characters. As it exists now, the film begins rather abruptly.

Whether these scenes from the synopsis were ever filmed, or were lost during the film developing process, or later during editing is unknown.

Today the film runs 17.18 minutes (including the 1953 titles), but a contemporary review stated the film was 1,000 feet long. It has been noted that it only requires 414 feet of film to run to 18 minutes (at 16 frames per second), so it is possible Paterson’s movie was much longer when it first premiered.

Click here to see the film on the Scottish Screen Archive website